Why are we talking about hydrogen now?

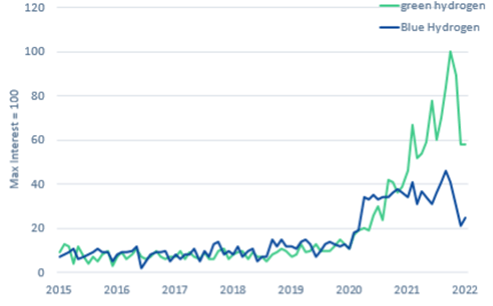

Hydrogen’s role in the energy transition has received increasing attention over the past 24 months, principally due to its ability to decarbonise hard to abate sectors, such as steel production, and balance intermittent power generation from renewables.

It is touted as the fuel of the future. It creates zero emissions at the point of burning and its distribution and supply can piggy-back off existing natural gas infrastructure.

Relative interest on Google Trends, max interest = 100

Energy transition savvy corporates, private equity sponsors, institutional investors and lenders are looking to gain exposure to this growth market either at the point of production or along the value chain, but the investment opportunity isn’t black and white – its green, blue, grey and all the colours in between.

Technical and environmental risks abound and choosing the wrong entry point could lead to failed or hard-to-exit investments further down the line.

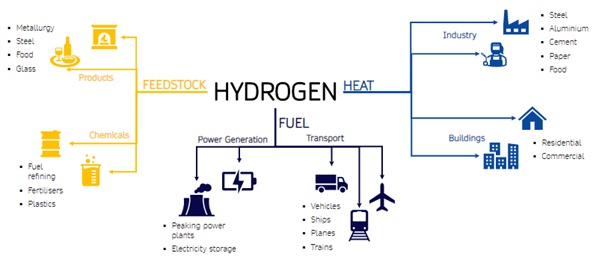

While hydrogen fuel cells have powered space flight since the 1950s, until now its commercial application as an energy source has been limited, with its primary use remaining as an industrial feedstock.

Current deployment of hydrogen

Calash has worked with a number of companies and investors to uncover short-term opportunities within the hydrogen value chain, but this requires getting to grips with a new, fast-changing, industry.

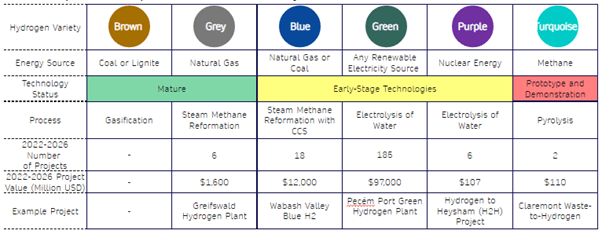

Splitting the hydrogen spectrum

Hydrogen comes in a bewildering array of ‘colours’ that denote its method of production. That produced from hydrocarbons without carbon capture, use and storage (CCUS) – grey and brown – are the most common forms today. Grey hydrogen as an industrial feedstock will dominate to 2030 but this method cannot be ramped up as part of a low-carbon economy.

Energy transition scenarios forecast supercharged demand for low-carbon hydrogen, with the current project pipeline leaning heavily toward green hydrogen produced from renewables-derived electricity.

Blue hydrogen, which is produced from natural gas stripped of its carbon, presents an alternative low-carbon hydrogen source, and is often positioned as a pragmatic alternative to green hydrogen. It is, however, at risk of falling outside the pale of ESG thresholds.

Alternatively, cheaper, low-emission, purple and turquoise variants, derived from nuclear electrolysis and biogas pyrolysis, respectively, could be key.

Hydrogen types and sources

Chasing the rainbow

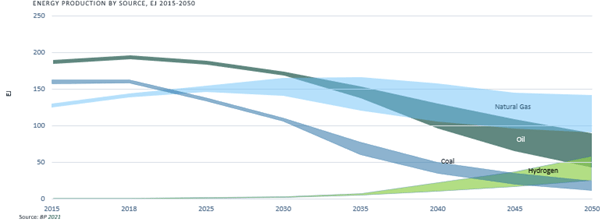

At present, investment in hydrogen is focused on pilot projects and technology development, with at-scale green hydrogen generation is not expected until the 2030s. Governments and utilities are assessing the cost of repurposing existing natural gas infrastructure to supply homes and businesses with hydrogen, but this will be time and capital intensive.

Hydrogen’s use as a fuel will be regionally driven by differing levels of existing energy infrastructure, as well divergent political and regulatory approaches. A mix of both blue and green scenarios will be needed to meet the challenge.

Hydrogen production is not expected to increase in scale until the 2030s

Is the golden ticket green?

Outside of North American, particularly in Europe, green hydrogen projects are attracting massive investment commitments because it is politically more palatable than blue, which requires parallel commercialisation of CCUS technology.

Forecasts suggest blue hydrogen could be more cost effective than green hydrogen, however, both are dependent on the costs of inputs, which could be highly variable, as seen in 2020-2021. The falling costs of renewable electricity weighed against increasing gas prices could change this dynamic.

Green hydrogen is only cost competitive with blue when it uses excess electricity that would otherwise be wasted.

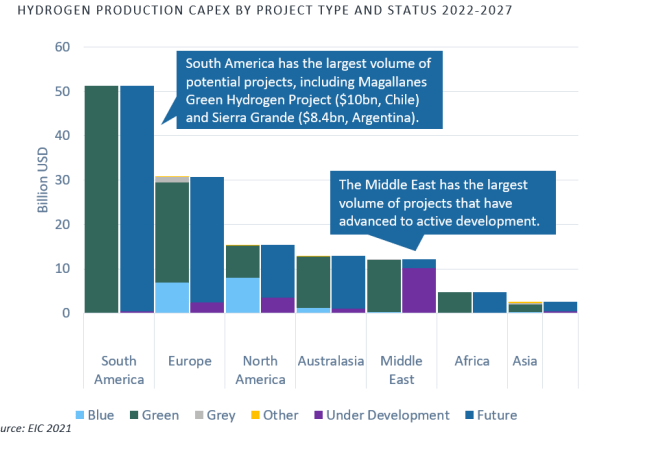

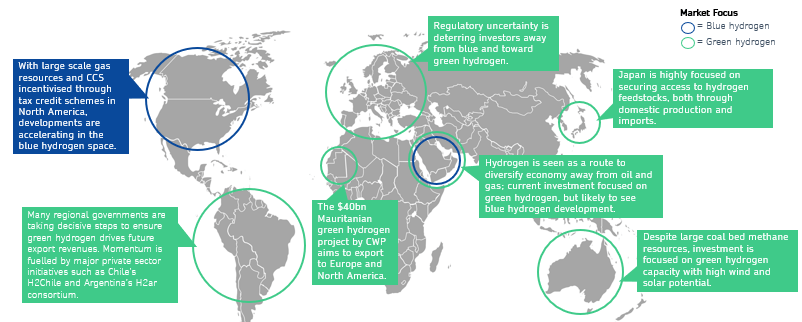

Europe and South America lead hydrogen investments, with a focus on green hydrogen

Fear of regulatory lockout has focused investment on green hydrogen, and as further technological developments are required for the commercialisation of blue hydrogen. The local resource base is also driving the choice between green and blue hydrogen, with high natural gas producing nations keener for blue hydrogen development.

Regional market positions

The deficit between electrification and hydrogen

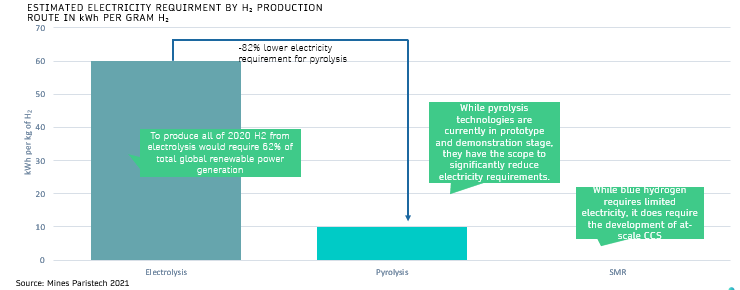

The demand for electricity will increase with electric-vehicle roll out and other electrification scenarios, against which diverting power to produce green hydrogen could be less cost efficient and lead to continued reliance on thermal power generation. Therefore, alternative technologies such as pyrolysis-based turquoise hydrogen could present attractive alternatives.

Electricity requirements are an important consideration when considering the global role out of hydrogen

The UK’s average grid carbon intensity in the first 20 days of 2022 was 175gCO2/kWh, while July 2021 saw a grid intensity of 210gCO2/kWh. Green hydrogen can only be commercially viable when produced during times of electricity surplus, but many electrolyser projects become unprofitable if deployed solely for intermittent usage.

Pragmatically, pyrolysis-based turquoise hydrogen could present an oft-forgotten third option. Pyrolysis can be inherently carbon negative as CO2 is captured in a char rather than being released as a gas, and can be applied to the existing biomass and waste-to-energy sector.

The opportunity

As a key pillar of the energy transition, the hydrogen value chain will absorb, and eventually generate, a lot of investment capital. The opportunity set depends on individual investor appetite for technical and ESG risk.

The largest market for hydrogen will be as an energy source, rather than as its current use as a feedstock, but this will take many years to reach critical mass. The medium-term opportunity is in its ability to monetise surplus renewable power and as a heating source, particularly in industrial clusters.

Green hydrogen requires significant additional investment in renewable power and expensive repurposing of grid infrastructure. While blue could be a more efficient means of production, it risks falling between the gaps of the climate debate.

Targeting investments in the production, and related technology, of either form of hydrogen has its risks, but could result in exposure to a sector with massive growth potential.

Ultimately, hydrogen as a fuel source for light vehicles and for homes does not stack up against the alternative benefits of electrification.

Other forms of production, such as turquoise, are less well known but could be an attractive, low carbon, means to displace the current demand for hydrogen as an industrial feedstock. This is an immediate opportunity but could become eclipsed as industrial-scale electrolysis becomes increasingly cost effective.

Calash is an international strategy consultancy that combines seasoned technical and commercial experts and deep sector experience to deliver winning strategies that enable our clients to accelerate value growth. Working across the energy, natural resources, marine, defence and industrial markets, our highly knowledgeable team takes a hands-on approach, delivering concise, tailored outputs and insights that are both pragmatic and commercial.