The dividing line between the chemicals and energy sectors has always been thin. Energy aside, the fact is that many of our most used materials are made from hydrocarbons.

The further downstream you go in oil and gas, the more it becomes the realm of chemicals, and vice versa. This dynamic has resulted in the development of the integrated oil majors we see today, where exposure to the full value chain has provided a shield against volatile commodity prices by passing off costs to the consumer by selling the finished product.

But now many majors are weaning themselves off their petrochemicals assets in a bid to unlock capital that can be reinvested into the energy transition.

BP sold its downstream oil business to INEOS for USD 5bn in 2020, followed closely by TotalEnergies selling its UK Lindsey refinery to Prax later that year.

Many multinational chemicals companies previously subscribed to the same integrated thinking, and themselves invested heavily in upstream oil and gas in a bid to gain a degree of supply chain control. They are likewise now trying to unpick the integrated business model, with varying degrees of success. Germany’s BASF, for example, has now found itself now stuck in its investment in Wintershall DEA, the upstream businesses co-owned with Mikhail Fridman.

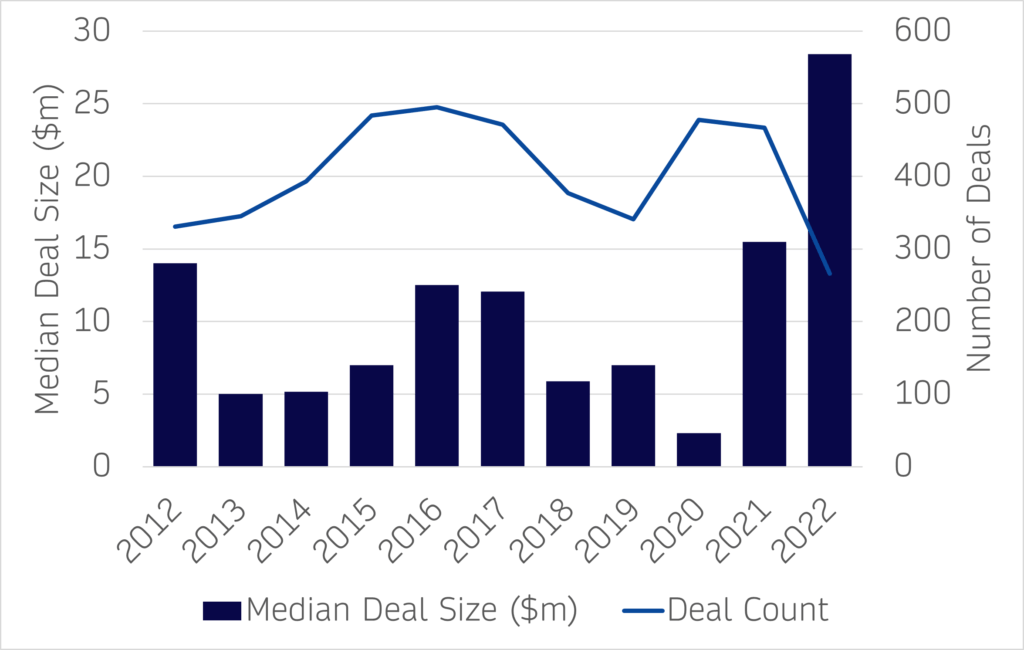

Industrial Chemical M&A Deals | PitchBook 2022

Chemicals in the energy value chain

The shifting of business models in the chemicals domain has been driven largely by the energy transition and the perceived ESG sin of hydrocarbon exposure. This is unlikely to abate, and oil majors will continue to realise value from their downstream operations, while the chemicals giants will increasingly shy away from links to the oil and gas industry.

This means at a macro-level seeking to reduce exposure to oil-based product manufacturing, and at a targeted level to cease the supply of chemicals used in oil and gas extractions.

Finding buyers for either scenario is a challenge. The pool of bidders is limited to those with an appetite for oil and gas, which naturally excludes many private equity investors, especially those in Europe, and corporates involved in the energy supply chain.

However, the demand for both oil and gas, for energy and materials, is not going away any time soon and consolidation in the space is about more than just managing decline.

Solvay and CMC Materials, for example, are both mooted to be looking at the sales of their multibillion-dollar oilfield chemicals units.

Investors are naturally wary of investing in a market with perceived limited growth, but these businesses are likely to be highly profitable in the current high-oil-price market, and their products will be needed in many upstream jurisdictions for decades to come, especially the US and Asia.

This means the bidder pool leans towards those with specialist knowledge of the two sectors and a long-term view of continued hydrocarbon demand, and will likely include sector-focused private equity houses and possibly trade players in the value chain, such as the large energy service and equipment companies.

But pitched right, these units could also appeal to generalist investors looking to play the energy transition. The targets could be approached in the same way that upstream oil and gas businesses are perceived. If there is an underlying acceptance that the hydrocarbon industry is not itself un-investable, the consideration comes down to whether the product makes the dirty business of oil and gas cleaner, or whether there any routes for diversification into new segments, such as renewables, carbon capture or hydrogen.

The same could be said of chemicals used in mining. If it’s making the necessary extraction cleaner, then it has a net positive impact on the environment, especially, in this case, if the commodity mined is used in battery technology or electrification.

The trick will be unpicking any greenwashing that might stick to these businesses, and validating assumptions on growth and new markets.

Chemical transition opportunity

There are already opportunities in the energy transition for private equity investors to pursue growth strategies aligned with ESG goals.

Lubricants, for example, are used across process industries, including power generation, and a supplier of these products can credibly shift from one untrendy customer base to another more fashionable. In the case of renewables, wind turbines and gearboxes require regular oil changes to remain operational and extend asset life. The growth of this market is on track to grow alongside the development of larger turbines and gearboxes.

Petrochemicals, such as plastics, can also play a role in cost reductions across renewable energy generation. As an example, in the wind energy sector, lightweight plastic-based materials can help address the challenges of manufacturing larger turbine blades, therefore improving generation efficiency. These materials can also help increase the durability of wind turbines and reduce the cost of maintenance. This will be especially beneficial for the harsh environments seen offshore.

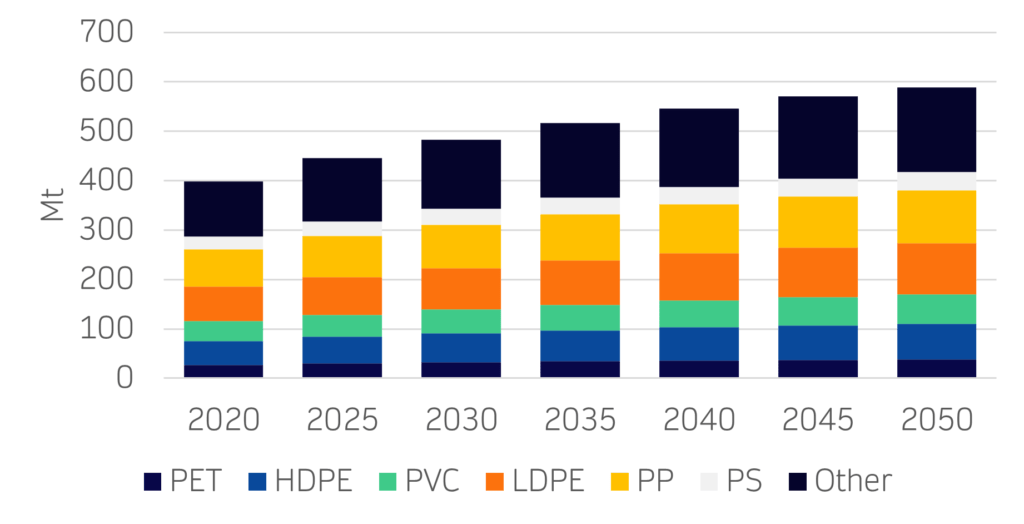

Production of key thermoplastics, 2020-2050 | IEA 2020

Electrification, particularly the roll-out of electric vehicles, will likewise catalyse a shift in the supply and demand of certain chemical products. Lubricants and oils aside, the chemicals industry will need to hike the production of transformer fluids, and the capacity to process battery materials such as lithium and cobalt.

This will spur the development of new technologies and products that will further drive investment down the value chain, and lead to M&A around those businesses demonstrating growth potential.

The other large area of opportunity is sustainable fuels – but this subject deserves a discussion all to itself.

Big ticket or small

Taking a step back, three sets of opportunities will likely arise over the coming years. Large, transformative divestments from the oil major and chemicals giants that will attract only the largest private equity houses and corporate bidders with a counter-cultural view of the energy market, such as non-Western and privately-owned peers, and possibly opportunistic commodity traders.

Below this will be the mid-tier divestments of smaller business units that may be specialised in a certain niche, hydrocarbon-facing, segments. Specialist funds and trade buyers are likely to dominate these transactions, which will normally include an energy transition growth angle that firstly requires an appetite for oil and gas.

If precedent sale processes are anything to go by, both larger and smaller transaction types will present a challenge for the vendor and their advisers. Johnson Matthey’s sale attempts of its diagnostics business Tracerco is a case in point, having yet to find a buyer.

But below these brackets will come the deals for chemical manufacturers and suppliers that offer products squarely aligned with the energy transition. These businesses will often be younger and smaller, but with the potential to access high-growth end markets, and as such will accrue weighty multiples.

Anyone seeking to execute deals in the chemicals space that are related to the energy market, whether that’s oil and gas or electrification, will be taking on energy transition risk. The energy market is always in a state of flux, but even more so now than in previous years, with the energy security concerns adding another layer to the transition, and making for unpredictable shifts in global demand-supply. This isn’t for the fainthearted.

Patrick Harris : James Kirby